There’s a lot of misinformation out there right now relating to so-called high resolution audio. Many large companies are now marketing audio products with this term, including audio systems, phones, headphones and speakers.

But what is high resolution audio exactly? Is it audio that’s provided at a higher sample rate or bit depth than audio CDs? Is it a particular frequency balance on headphones? Is it to do with how the audio was recorded and mastered?

The Real Problem: The Loudness War

What many fail to disclose is that the most fundamental problem with audio quality today is the way that it’s mastered and an issue known as The Loudness War.

Mastered for iTunes tracks for the most part are unaltered from their original masters. Even stores like HDtracks often sell 24-bit music based on the same master that was released on CD and other digital stores. However, to give some credit to HDtracks, they are sometimes provided better masters, which do sound significantly better than the original masters.

If you don’t know what this war is about, I suggest that you watch the video What famous producers think about the Loudness Wars which explains the problem very clearly and accurately.

The main points are as follows;

- Almost all music released today (particularly in genres such as pop, rock, EDM and country) are mastered to sound as loud as possible.

- Maximising loudness is usually performed by a combination of dynamics compression, peak limiting and clipping all of which degrade the original audio source.

- This is often done because people believe that louder records sell more, even though this has never really been proven. In other cases, this is done to simply conform to what other similar artists are doing.

I wish I could say that I didn’t take part in producing loud masters for my Sonic Element releases, but much like all other trance artists, I did. I typically only used clipping on my masters though and avoided any compression which still lead to my masters sounding dynamic but somewhat squashed.

I hope to remedy that soon for any releases I have the rights over. Keep an eye on my Twitter page for news about this.

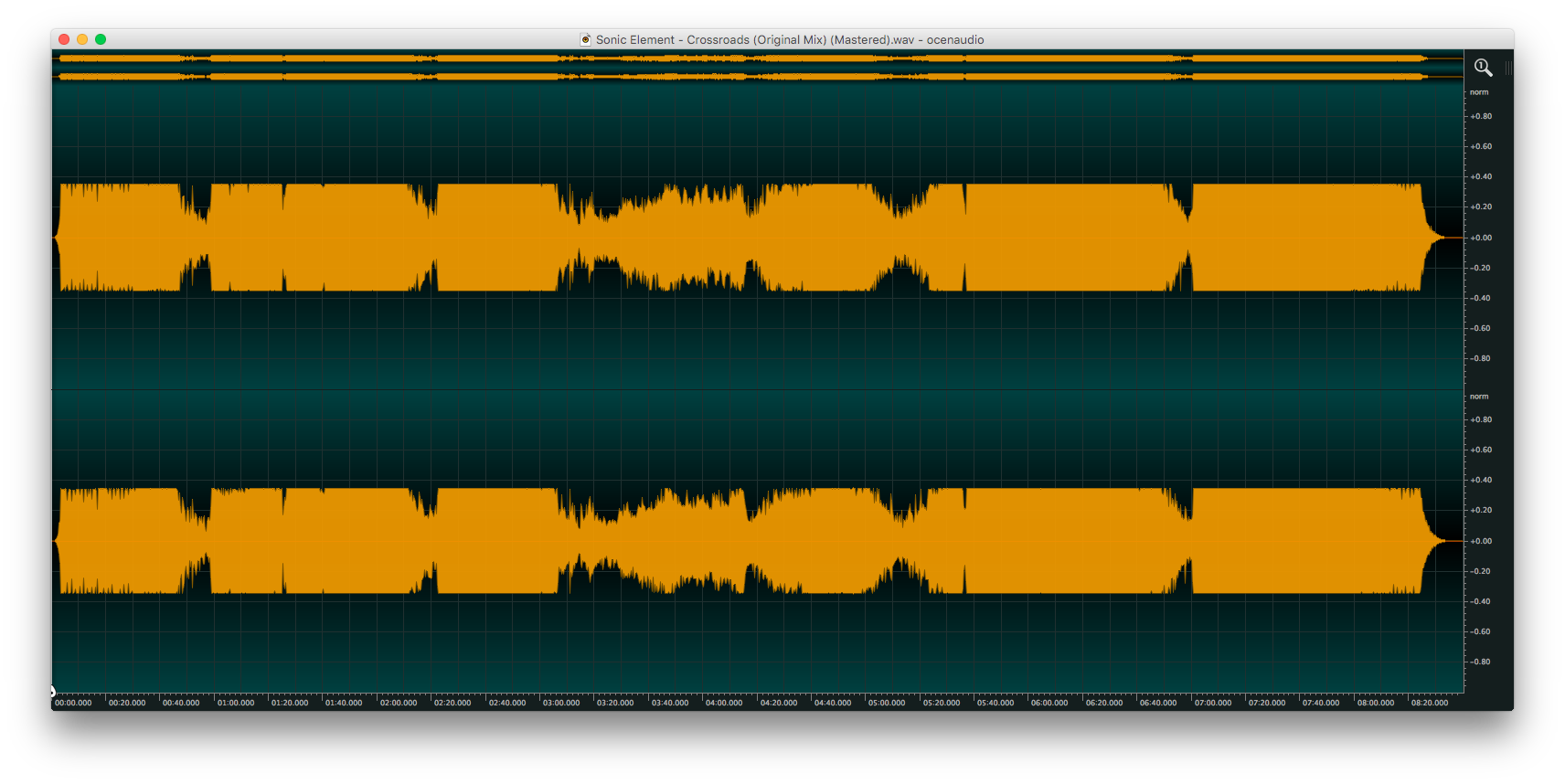

To give you an idea, here’s how my released master of Crossroads looks:

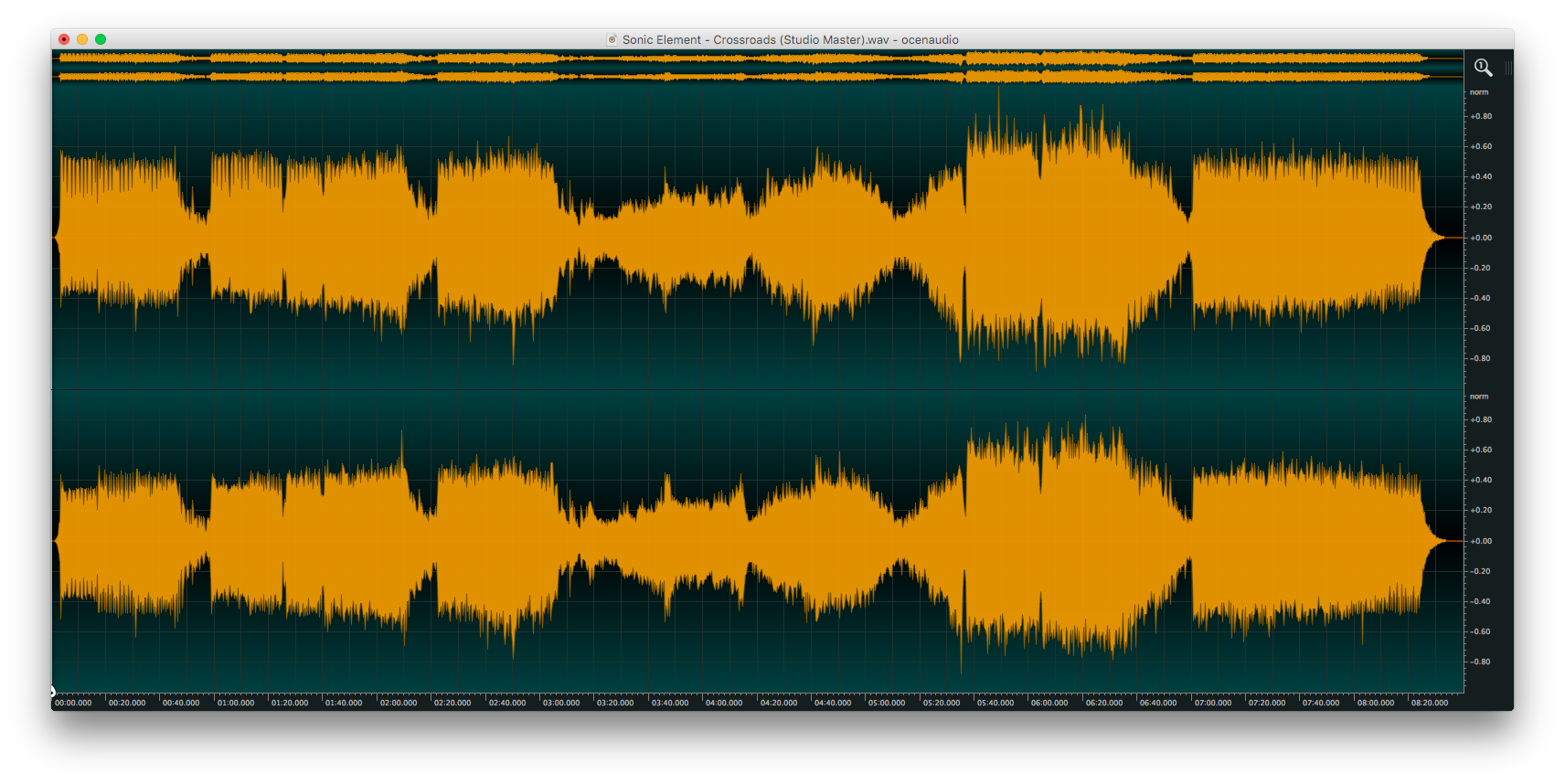

And here’s what it looks like mastered without regard for the loudness war:

In my honest opinion, if mastering engineers continue taking part in the loudness war, there’s almost no point of high resolution formats or even lossless formats for that matter.

Compression & Peak Limiting

To most music-lovers, the word compression is associated with MP3s and other compressed audio formats. However, the word compression is also used for a type of digital signal processing (DSP) known as dynamics processing.

What compression does is bring down louder parts of audio and bring up quieter parts so that you may have a more consistent volume throughout.

While this is a very important technique on individual instruments and sometimes groups of instruments (e.g. drums), applying moderate to heavy compression to an entire mix (which is often done during mastering) usually leads to tracks sounding lifeless and lacking variation between loud and quiet parts.

Peak limiting is a significantly more aggressive version of compression, where the audio is not allowed to exceed a particular threshold set by the engineer. Any audio above this threshold will be heavily compressed back down to ensure it is below the threshold set.

Clipping

Clipping is often used during the mastering process as an even more extreme version of peak limiting. With clipping, the signal is not lowered below the threshold, instead it is allowed to exceed the threshold which leads to digital flattening of the signal beyond that point.

The reason that clipping is often used is that it can lead to louder masters and preserves transients such as drum hits much better than peak limiting with the trade-off being more distortion.

Have Streaming & EBU R128 Changed The Situation?

Streaming music services such as Spotify and Apple Music have started to change this landscape recently. Spotify employs loudness normalisation by default which calculates the loudness of songs and volume matches them so that loud masters actually sound dull by comparison to dynamic masters. Apple Music does this via an opt-in feature known as Sound Check.

Sadly, Spotify also performs some extremely low quality peak limiting when their loudness normalisation is turned on, so I suggest disabling it. Apple’s Sound Check is a significantly superior implementation.

The recent EBU R128 standard for measuring audio loudness has also given us a much more accurate way to measure a song or program’s loudness and the recent AES TD1004.1.15-10 recommendation for music and streaming also provides a very good standard for music loudness.

Listeners and mastering engineers are more openly talking about the loudness war and have even started a petition called Bring Peace to the Loudness War.

What About Higher Bit Depths & Sample Rates?

Many people suggest that higher resolution audio formats are not important and that their benefits cannot be perceived by humans. This is somewhat true with a few important caveats:

-

Recording: Higher resolution formats are extremely beneficial during recording and mixing.

Most analog to digital converters which are used to record digital audio have a dynamic range greater than 16-bit used on CDs and due to the fact that audio is heavily processed afterwards during mixing, this extra information can lead to a more transparent sounding track. This is particularly important with dynamics processing, where quiet portions of the recording are brought up in level along with their noise floor.

-

DSP & Synthesis: DSP used in signal processing and synthesizers can be prone to issues at sample rates that extend just beyond our hearing (e.g. 44.1 kHz). Many such processors actually use internal upsampling to process audio at double the sample rate and then convert it back down again.

As such, poorly designed DSP and synthesis algorithms (which there are many) that aren’t upsampled do sound inferior at lower sample rates.

-

Downsampling: Recording at a higher sample rate requires you to downsample when producing a 16-bit / 44.1 kHz version for CD and most digital sites.

If you record at exactly double the target sample rate (e.g. 88.2 kHz), this is far less prone to issues as you can downsample the original recording more transparently. However, when downsampling 96 kHz to 44.1 kHz, you must approximate sample values based on their neighbours. There is an entire site dedicated to testing sample converters and not all are made equal.

-

Dithering: Recording at a higher bit depth requires you to dither the audio when converting to a lower bit depth.

Although not quite as troublesome as sample rate conversion, dithering algorithms and variables such as noise shaping can play a role in the quality of the resulting audio.

If care is taken, a 16-bit / 44.1 kHz master can sound every bit as good as the final studio master.

However, with even many consumer DACs supporting 24-bit / 96 kHz these days and internet speeds getting faster and faster, there’s absolutely no harm in distributing higher resolution formats. But they won’t necessarily sound better unless the dithering and/or sample rate conversion used is of a particularly low quality.

I would take a well mastered 16-bit / 44 kHz master over a clipped 24-bit / 96 kHz master any day of the week.

What About Compressed Audio Formats?

There’s also a huge amount of debate on whether lossless formats such as FLAC and ALAC sound better than high-bitrate lossy MP3, OGG and AAC files.

Personally, I find 320 kbps LAME MP3, OGG and Apple AAC encoded files completely indistinguishable from the original source. However, I encourage you to take a FLAC file you own, convert it to the desired format you wish to compare against and perform a true blind AB comparison using something like foobar2000’s ABX Comparator.

If you can genuinely pass this test, then you have exceptional hearing and should opt for lossless audio if you can.

Similarly to the point above, there’s absolutely no harm in having a lossless version of your music. Storage is cheap and bandwidth is readily available, so I would always choose a lossless file over a lossy file given the choice. But it’s nothing worth losing sleep over.

I would take a well mastered 320 bkps MP3 master over a clipped lossless master any day of the week.

So Then What Is High Resolution Audio?

To me, high resolution audio is first and foremost audio that has not been mastered using dynamics compressors, peak limiters or clippers. It is music that has been well written, produced, mixed and mastered.

I believe that an audio system or phone is high resolution if it offers a clean and flat frequency response when reproducing the source with no noticeable noise.

Unless a pair of headphones or speakers contain a DAC built in, their claim to be high resolution is quite confusing.

Headphones and speakers which are close to having a neutral (flat) frequency response, excellent stereo imaging, fast transient response and excellent detail are what I consider to be high resolution.

At what point does a pair of headphones or speakers become high resolution? I’d say at the point which studio engineers feel that they are a good second reference for their mixes and masters.

Let’s hope that we see a dramatic shift in mastering over the next 5 - 10 years and we all realise that we have destroyed decades of music for no apparently good reason.

Feel free to ask questions and engage in friendly discussions on this topic below :)